Click here to download the complete article as a PDF document.

1. Context of Health Coverage in the United Kingdom

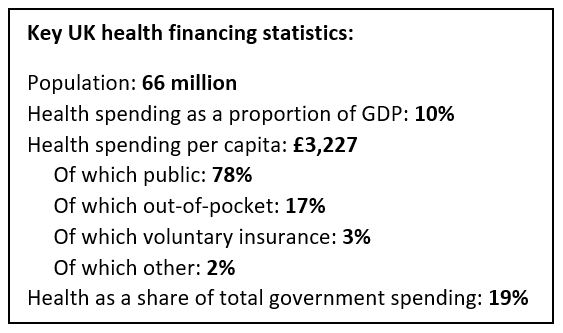

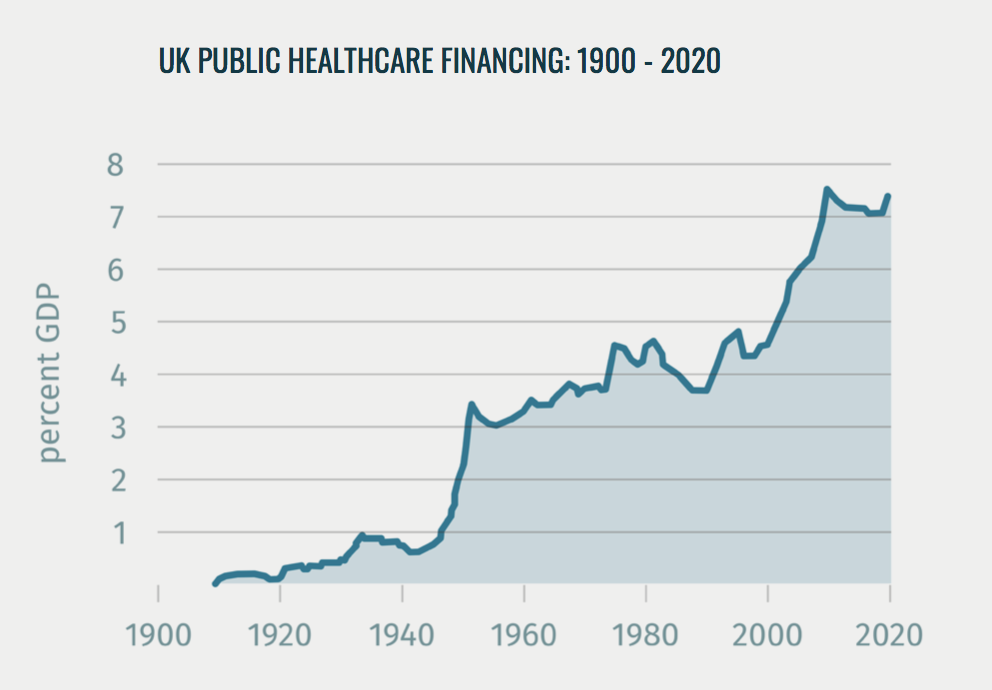

The UK National Health Service (NHS) was founded in 1948 and remains the dominant system of health coverage today. It is financed primarily through general taxation (80 percent), supplemented via a payroll tax. The overall budget is controlled by the Treasury, and public funding – which makes up around 78 percent of all health funding in the UK – has tended to rise at levels above economic growth and inflation: around 3.5 percent a year over the 70 year history of the NHS, albeit with significant swings.

Every UK resident is entitled to care funded by the NHS, although migrants with ‘temporary leave to remain’ have had to pay an additional surcharge since 2015.

The benefit package is implicit but very broad (defined as “comprehensive” in law), including most primary, secondary, tertiary, community and mental healthcare treatments. There are some restrictions, which vary by local area, in drugs and procedures deemed low value, with new treatments subject to a transparent process of health technology assessment. Social care is largely not available as a benefit on the NHS, or only through a means test, although some personal care services are available at no or minimal cost in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

NHS services are available almost entirely free at the point of use. The only exceptions are small co-payments on outpatient and primary care drugs and appliances in England (for which almost 90 percent of prescriptions are exempt for one reason or another)[1], as well as charges for routine dentistry and optometry.

Administration of the NHS is devolved, and the different home nations have pursued divergent strategies over the role of government as payer, provider and regulator/steward of the system. England and Northern Ireland have a purchaser-provider split, with the former having overall strategy set by government and day to day administration via an quasi-autonomous agency, NHS England, whose duties include planning and purchasing highly specialized services such as rare disorders and prison health. Most planning and purchasing decisions in England are made via 135 local ‘Clinical Commissioning Groups’, led by groups of family doctors – although there are ongoing plans to consolidate this number and shift their role more towards strategy and system oversight (See page 9). An array of other national and regional arms-length bodies exist to perform quality and financial regulation, public health, workforce planning and other functions. However, the overall cost of administration of the NHS is comparably low, 2.4 percent of health spending compared to an OECD average of 3.2.[2]. Scotland and Wales operate a much more direct system of government control for NHS planning, purchasing and provision via NHS Wales and NHS Scotland.

In terms of provision, most hospital, ambulance, mental health and community care providers are owned by the state, although in England around half have been awarded ‘foundation trust’ status, which gives them a degree of autonomy from central control. Most general practices are independent private providers operating under nationally agreed contractual terms. Payment models for hospitals have been based predominantly on a form of diagnosis-related groups but there is a movement back to more block contract models of payment in response to attempts to create integrated care and reduce the incentives to admit patients for conditions related to chronic disease. Primary care is paid on a capitation basis, but with significant amounts tied to pay-for-performance schemes.

Private providers and insurance both operate within the UK healthcare system, but make up a relatively small share of expenditure and activity. Around 10 percent of the population hold voluntary private insurance[3] – mostly corporate policies provided by their employer – however these only account for around 3 percent of health spending[4]. Private providers do a mix of NHS-funded and non-NHS funded work, and account for around 7 percent of NHS-funded activity in England, and substantially less in the other home nations[5]. The NHS itself also provides various private services to patients, for example offering better quality rooms, treatments not funded on the NHS, and to avoid waiting times.

2. A Timeline of Health Care Financing and Coverage

This history of health financing and universal coverage in the UK can be subdivided into four periods, described below:

- Pre-1911: Growing role of the State in social protection and public heatlh

- 1911 – 1939: Coverage for workers and increased funding to patch up the gaps

- 1945 – 1975: The creation and consolidation of the NHS

- 1975 – Present: The quest for high quality care for all

Pre-1911: Growing role of the State in social protection and public health

While the 1911 National Insurance Act was the UK’s first large scale legislation for the government to mandate health insurance coverage for a significant proportion of the population, there were several important antecedents in the prior century – and beyond – that helped to lay the foundations.

Poor Laws were first enacted for England and Wales in 1598 and 1601, ushering in a major expansion of state-directed social security. They established for the first time an individual ‘right to relief’ for all citizens. Progressively financed through a new tax based on property values and administered by local parishes, these laws created a safety net for key vulnerable groups such as orphans, widows, older people and people with disabilities[6]. The benefits varied depending on status and ability to work but generally involved the provision of food, accommodation and basic medical care within prescribed institutions. Through the Charitable Uses Act of 1601, the Poor Laws also initiated a large-scale building of local hospitals and schools, funded by philanthropic spending that was deducible against the Poor Law levy[7]. The program was vast in scale in comparison to other countries at the same time, representing 1 – 2.5 percent of national GDP per year during the 18th and early 19th centuries[8].

The 1834 reforms to the Poor Laws fundamentally changed their legal basis, transferring the role of the state from mandating the right to relief through a largely church-centred and administered system to one in which the government itself was responsible for the welfare of the poorest citizens[9]. This was partly in response to rapid urbanization following the industrial revolution, which meant that local parishes were no longer an effective risk pool or means of administering fast-changing demography and patterns of need.

This shift in responsibility gradually created an incentive for government to invest in prevention of poverty and poor health – partly to contain the cost of the new poor laws – leading to the 1848 Public Health Act. This recognised for the first time an explicit responsibility on the part of the state for disease prevention and health promotion. The Act contributed to one of the largest periods of government investment in public infrastructure such as sanitation, housing and green spaces in British history over the following half century, enabled in part by rapid economic growth during this period[10].

1911 – 1939: Coverage for workers and increased funding to patch up the gaps

By 1900, the UK had a mixed system of healthcare financing and provision that left a great many gaps in effective coverage. Around half the working population was covered by some form of voluntary or employer-assisted health insurance via friendly societies or sector-specific schemes – these typically covered the majority of costs for routine care by a general practitioner, with some co-payments at the point of service[11]. Doctors and hospitals also ran their own subscription clubs whereby families could pay a voluntary weekly fee to cover the costs of treatment when needed. Charity also played a prominent role, with legacies, donations and investment income providing the largest source of revenue for the 800 voluntary hospitals that existed at that time, and which would provide free care for selected groups such as low income families, and on a fee-paying basis for others[12]. Poor law institutions funded by the state (such as workhouses) were another key provider for the less well off, though the services were of low quality and often stigmatized[13].

The first half of the 20th Century saw two somewhat competing ideologies of social protection operating in parallel – one based around healthcare as an individual entitlement to be secured through social health insurance, and the other based around the idea of a collective or universal right to health[14].

1911 saw the passing of the National Insurance Act, which created the first major state-sponsored, compulsory, contributory system for around half of the adult population. The system was modelled to some extent on the Statutory Health Insurance introduced in Germany in 1884 by Otto von Bismarck. It was offered to manual labourers and salaried workers earning under a certain threshold, but did not include their dependents, informal sector workers, the middle class or many other groups. The benefit package covered primary care, pharmaceuticals, treatment in residential sanitoria (for tuberculosis) and sick pay during periods of illness or disability. Unlike equivalent Social Health Insurance schemes in other countries during this period, the NHI did not cover hospital services, as this was deemed unaffordable. Unemployment insurance was also included for some workers in cyclical occupations, as well as maternity pay for women. The system was contributory, with most employees paying fourpence per week, which was matched by threepence from their employer and two pence from the government[15]. Lower contributions were required of workers earning less than the threshold salary, using a sliding scale.

A limited system medical savings accounts were also created for workers unable to find an insurer to cover them (e.g. on the grounds of poor health status). These were administered by the Post Office, but were significantly less popular, covering around 200,000 persons[16].

There was a dual system of administration for the national insurance system, with cash benefits, premium collection, record keeping and membership functions performed by a patchwork of trade unions, friendly societies, ‘sick clubs’ and commercial insurers operating as Approved Societies. These were self-governing – but regulated – insurance funds that had to operate not-for-profit but could refuse to cover an individual on any grounds apart from age. Medical benefits were administered by National Health Insurance Committees – local bodies of 40-80 members representing workers, doctors, local authorities, and other delegates appointed by the Ministry of Health. These were responsible for negotiating with and maintaining lists of an approved panel of doctors and dispensaries, which beneficiaries could choose from. The system operated under separate oversight arrangements in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland with small differences in policy and practice.

This national insurance system underwent various reforms throughout the 1920s and 30s to enhance the benefit package, increase enrolment, reduce the government contribution, reduce the capitation and fee rates for doctors, and allay concerns about ‘malingering’ in various ways. However, by and large it remained in place for the employed population until the creation of the National Health Service. Coverage was never extended to hospital services, and so an increasing number of workers – five million by 1936 – paid into voluntary hospital insurance schemes, which usually covered a household rather than an individual[17].

During the same period, rival beliefs about the universal right to health coverage were also gaining ground, but in a more ad hoc way through piecemeal increases in public funding for a growing patchwork of free or low cost health services, often targeted at specific groups such as special hospitals and welfare clinics for women and children, or vertical programmes such as for tuberculosis sanitoria, fever or mental hospitals[18]. Throughout the 1920s and 30s some local authorities also began putting significant funding into voluntary hospitals to bolster their frequent deficits and ensure continued hospital provision for the poorest in their communities[19].

One major legislative milestone was the 1929 Local Government Act, which partially repealed the 1834 Poor Laws and gave local authorities the powers to take over poor law institutions such as infirmaries and workhouses and develop them into modern general hospitals – this was a key expansion in the responsibility of the state from health promotion to medical treatment, albeit only for particular groups.

Two other important developments in this universal trend during this period were, first, the creation of the Highlands and Islands Medical Service. This was founded in 1913 to cover 300,000 people across some of Scotland’s most remote communities[20]. As a state- subsidized, comprehensive health service under the direct control of the Department of Health for Scotland, it was many respects a forerunner of the future National Health Service. Secondly, the increasing role of volunteer first aid services, such as the British Red Cross and Order of St John, that been founded during World War I and came to be responsible for much of the national ambulance service in the decades running up to the creation of the NHS[21].

1939 – 1975: The creation and consolidation of the NHS

In the run up to and during the Second World War, a remarkable consensus emerged across different political and medical actors of the need to consolidate the haphazard patchwork of coverage schemes across the UK into some form of national, universal system of health coverage[22]. A number of factors contributed to this consensus for change, including[23]:

- The complexity of navigating different benefits, payers and providers and understanding which services a person was entitled to. This mix included the national insurance system, means-tested voluntary hospitals, individual subscriptions to GPs, old poor law institutions some of which were now operated by local authorities, various voluntary contributory hospital insurance schemes, and out-of-pocket services – the latter of which still made up around 7-8 percent of a middle class families expenditure before the outbreak of World War II[24].

-

A heightened sense of social solidarity during and immediately after the war, which clashed with a perceived unfairness in the treatment given to fee-paying versus subsidized patients. There had long been a perception that doctors could give differing standards of care to patients based on their payment and coverage status, for example in the 1924 agreement between the British Medical Association and Ministry of Health on panel doctors’ pay it was agreed that although national insurance payments would make up an average of half of panel doctors’ pay, they would only be expected to spend two sevenths of their time with these patients[25].

-

The Depression of the 1920s and 1930s having exposed deep health inequalities, followed by the increasing bargaining power of labour unions during World War II[26].

-

An Emergency Hospital Service (EMS) implemented and run by the national government during World War II to care for casualties, essential workers, evacuees and many other groups. This demonstrated that a coordinated, comprehensive and universal service might indeed be feasible. The EMS was a combination of requisitioned beds from existing hospitals and a rapid programme of hospital building, with services coordinated centrally by the Ministry of Health.

-

The increasing cost of new medical treatments being developed through scientific advances, which were increasingly out of reach for average households.

In 1941 the Treasury commissioned a study by a committee chaired by Sir William Beveridge to examine the possibility of a simpler system of social protection. The resulting report Social Insurance and Allied Services went much further than anticipated in its recommendations, and set out a vision for a comprehensive system of health, education, employment, housing and social security all guaranteed and in many cases funded by government[27]. The aim was to simultaneously slay what the report called the ‘five giants’: “want, ignorance, squalor, idleness and disease”. The health recommendations set out the foundations for what would become known as the Beveridge Model: tax financed services, free at the point of use and accessible to as a universal right rather than via contributions.

The then-ruling Conservative Party made the first attempt to design a detailed model to operationalize Beveridge’s vision – the White Paper A National Health Service was published in 1944 with cross-party support. The plan involved a major expansion of the already-growing role of local authorities for healthcare and public health, by giving them primary responsibility for planning, administering and purchasing healthcare provision for their local populations – but avoiding “unnecessary uprooting of established services” by maintaining the mixed landscape of state and non-state providers. The plan took care to try and satisfy the many competing interests of powerful actors in the system, such as the medical establishment, non-state hospitals and local authorities, but nonetheless faced fierce resistance from multiple angles[28].

With the large parliamentary majority of the new Labour government in 1945, however, this deadlock was broken and an even more radical plan was put forward and implemented through the National Health Service Act 1946. Health Minister Aneurin Bevan rejected many of the compromises and complexities of the Conservative plan and instead pushed forward a model whereby the state would be dominant purchaser, planner and – for secondary and tertiary care – provider of healthcare for all citizens through universal, tax-financed National Health Service. Hospitals would be nationalized so that both municipal and voluntary hospitals would all be under the control of the newly formed NHS to plan and manage. General Practitioners successfully lobbied to remain independent private practitioners contracted to provide services for the NHS, but not be employees of it.

This new system for England and Wales would be administered not by local authorities but by 14 dedicated, semi-autonomous Regional Hospital Boards (RHBs) responsible for service planning and financing within their boundaries, and run by local representatives of the medical, nursing, trades union, local authorities and other communities. Hospitals were administered by 388 Hospital Management Committees, working to plans set out by the RHBs, and with significant additional independence afforded to teaching hospitals, who were given 36 separate Boards of Governors with their own lines of accountability to the Ministry of Health. Local authorities were left with some residual responsibilities, including ambulance services, immunizations, some health centres, and community midwives, nurses and health visitors. Parallel systems of administration were put in place for the other home nations through the National Health Service (Scotland) Act 1947, administered by the Department of Health for Scotland, and the Health Services Act (Northern Ireland) 1948 under the Northern Ireland Parliament.

The scope of benefits was not made explicit but merely defined in the law as “comprehensive”. The financing for this new system was to come almost exclusively from government, apportioned to each region and hospital more or less in line with existing spending patterns. There was a perception that the service would be require a higher level of spending in the initial years while it dealt with the backlog of existing diseases in the population, then reduce to a more manageable level. This turned out not to be the case, leading to costs being significantly higher several years into the scheme than had been anticipated, fuelled by population ageing, advances in medical technology and rising patient expectations[29].

Attempts to contain these rising costs took the form of the introduction of some limited copayments for prescriptions, routine dentistry and spectacles, levied in 1952. While thesewere very modest, it was viewed as a violation of the NHS’s ‘free at the point of need’principles by some of its founders, including Nye Bevan who resigned from the Cabinet in protest.

Cost containment and efficiency measures continued to be a focus for much of the NHS’sfirst decade, although these fears were significantly allayed by the 1956 Guillebaud Committee report, commissioned by the Treasury. This used international comparisons and measures of health spending as a proportion of GDP to show that, in fact, the NHS was comparatively cost-efficient, and that projected levels of spending increases for the coming years could in fact be more than financed by expected levels of economic growth.Nonetheless, periodic reviews and reforms were undertaken to restructure the NHS’shospital, regional and local management tiers in the search for a more optimal administrative architecture that could achieve the highest standards of quality for all, at the same time as demonstrating efficient use of the growing share of public spending.

From a coverage perspective, some of the most important reforms during the early decades of the NHS were the consolidation of different health services initially left out of the Bevan model into the overall remit of the NHS. These included:

-

The 1973 NHS Reorganization Act, which instituted a major consolidation of healthcare powers within the NHS, moving public health, ambulances and community healthcare responsibilities, as well as the provision of school health services away from local authorities and into the NHS for the first time. It also abolished the tripartite administrative divisions between various hospital, family practitioner and personal health service boards and bodies under a single, unified system of leadership led by 14 Regional Health Authorities and 90 Area Health Authorities.

-

The 1959 Mental Health Act, which laid the legal foundations to integrate psychiatry and mental healthcare as an integral part of the NHS mandate, and phased out the previous system of segregated treatment and separate administration of psychiatric hospitals[30]. Local authorities were given responsibility for non-medical care services such as housing and training of people with a mental health disorder[31].

-

Less successful, and still an unsolved question as to the limits of the UK’s universalhealthcare system, was the attempt to begin integrating social care services into the NHS ‘benefit package’, through the 1968 merger of the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Social Security into the Department of Health and Social Security. However, beside some additional joint working this did little to span the growing chasm between the universal and comprehensive health service, and the much less generous social care system.

1975 – Present: The quest for value and sustainability

While the substantive work of creating a system of universal health coverage in the UK was achieved through the creation and consolidation of the NHS, ongoing reforms over the last 50 years show that this UHC journey is never fully complete. A number of recurring themes cycle round in the various laws and internal reforms to the system that have been made since, many of which reflect questions which all health systems must contend with to achieve available, acceptable, accessible and high quality healthcare for all over the long term.

1. Resource allocation: efficient or underfunded? Centralized control of NHS spending allows the UK a high degree of control over how much is spent on healthcare. International comparisons frequently report the cost efficiency of the UK model, in terms of the outputs and outcomes it produces for comparably less money than many equivalent countries[32]. There is a constant debate around the point at which efficiency is in fact underfunding, and whether the NHS is staying true to its vision not only to provide a basic safety net, but a service that offers the highest quality treatment to everyone, regardless of wealth or status. Important milestones in this debate include:

-

The 1976 report of the Resource Allocation Working Party, which for the first time used health econometric methods to demonstrate the internal inequities in health funding between richer and poorer regions, and proposing a weighted population formula that was then used to gradually equalize this over the next decade.

-

The Health and Social Care Act 2001, which expanded the ability of NHS providers to renew their ageing infrastructure through two public private partnerships structures: the Private Finance Initiative (for hospitals) and Local Improvement Finance Trust (for clinics). Dozens of new hospital facilities and hundreds of new clinics were built through these mechanisms, though there are criticisms of high interest rates and inflexible terms offered by the private sector partners.

-

The 2002 Wanless Review of the long-term funding needs of the NHS, which recommended an unprecedented period of spending growth in which much of the gap between the UK and its European neighbours in terms of health spending is closed: increasing health spending by almost 2 percent of GDP from when the review was published to when the Labour government left office in 2010. This was in part funded by an increase in the existing National Insurance payroll tax.

-

The 2009 announcement of the ‘Nicholson Challenge’ to improve quality while at the same time making roughly 5 percent saving on the NHS’s annual budget. This heralded a decade of unprecedented spending restraint on the service, though health was protected in comparison to many public services during the UK’s ‘age of austerity’.

-

The 2018 five-year funding settlement that saw the NHS return to increases in real terms spending, yet still below what health economists project is needed to keep pace with rising demand from an ageing population over the same period[33] [34].

2. The scope of the NHS ‘benefit package’: While the NHS model is one of assurance rather than insurance, in that there is no strictly defined national benefit package, like all systems there is a constant debate over which treatments should and should not be funded on the state. Three important milestones in the reforms on this theme include:

-

The 1998 creation of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), which was intended to de-politicize the “what’s in, what’s out” decisions for new drugs andtreatments through a transparent and largely quantitative process using Health Technology Assessments and an explicit cost-per-QALY affordability threshold.

-

The 1991 Patient Charter and 2009 NHS Constitution for England and Wales, and 2011 Patient Rights Act for Scotland, which sought to enshrine specific rights for NHS patients, including maximum waiting times for treatment.

-

Multiple reviews of the extent to which social care should be funded through the NHS, including a Royal Commission on Long Term Care in 1999, and 2011 Commission on Funding of Care and Support. These have tended to recommend that social services be much more closely integrated into the NHS benefit package. However, the cost involved – almost certainly requiring a significant new tax – has always proved a deterrent to action. While Scotland’s policy is somewhat moregenerous, social services in the UK remain privately funded for all but a minority of people who qualify through means-testing.

3. Market mechanisms and the role of the state as provider: Many reforms to the UK NHS over the last 30 years have sought to introduce or repeal market-based elements to the way that healthcare purchasing is done. The largest change was the creation of a purchaser provider split, or so-called ‘internal market’ through the NHS and Community Care Act 1990, which sought to break up the perceived conflict between the NHS taking planning and purchasing decisions as well as running most hospital and community services. This was thought at the time to be standing in the way of patients’ interests and leading to a tolerance of inefficiencies. While Scotland (2004) and Wales (2009) eventually repealed this division as inhibiting collaboration and introducing too great an administrative cost, England persisted until very recently to increase the role of competition as a tool for improvement. Market-style mechanisms introduced during the 21st century include the introduction of pay for performance schemes for hospitals and general practice. Also the gradual expansion ofpatients’ legal right to choose from any provider meeting NHS requirements, and commissioning of healthcare services from non-NHS providers – both designed to create adegree of ‘constructive discomfort’ among NHS trusts.

More recently, however, the English NHS has sought to reverse many of the rules aroundthe ‘internal market’, under concerns it was hindering integrated care. The 2019 NHS LongTerm Plan frees local payers from the requirement to follow strict procurement rules, and instead introduces a ‘duty to collaborate’ across providers and commissioners. New Integrated Care Systems – partnerships between NHS payers, NHS providers and local authorities across a defined geographical area – will cover all of England by 2021. This marks a major shift towards cooperation rather than competition as the primary lens for improvement over the coming years.

4. The optimal configuration for payer power: The English NHS has been through multiple reorganizations and reconfigurations of the agencies that undertake purchasing, or ‘commissioning’ decisions – moving through Area Health Authorities (1973), District Health Authorities (1982), Primary Care Groups (1999), Primary Care Trusts (2001), a wholesale merger of Primary Care Trusts (2006), Clinical Commissioning Groups (2013), and others. This seeming inability to find a satisfactory level at which to take local purchasing and planning decisions stems from several conflicting priorities, including the desire to control the increasing share of public spending that goes towards the NHS, to have locally accountable and responsive decision making, to increase clinical input in purchasing decisions, to coordinate healthcare planning with that of social care (which is run by local authorities), and to have efficient payer organizations that are able to leverage scale. In 2012 the system underwent a major reorganization which put around 200 groups of local general practitioners in charge of much of the NHS budget, while for the first time creating a quasi-independent agency – NHS England – as the primary national payer and planner of healthcare. The intention was to further reduce the role of government to that setting the strategy and ‘rules of the game’. However, the 2019 NHS Long Term Plan also sees many key elements of this reorganization undone – with Clinical Commissioning Groups likely merged to around 45 in number, and with a role defined more strongly in terms of population health management and less around purchasing. In this model more responsibility for the design of pathways of care will be taken by providers with purchasers focussing on outcomes, some key process indicators and major strategic decisions (such as the location of key services).

3. Conclusions

The foundations, establishment and subsequent reform of the UK NHS offer a host of lessons for other countries on the path to achieve and then sustain universal health coverage. Three observations in particular stand out from the timeline described above.

Firstly, universal health coverage can be extremely politically popular – as the continuation of the NHS after 70 years shows, with public surveys indicating it still achieves high levels of public satisfaction and is one of the features of British society that makes its citizens most proud [35] [36]. While various stages in the UK’s UHC journey were enabled by periods of economic growth and social solidarity, progress towards UHC also itself catalysed these things at times. The fact that the most decisive step in 1945 came at a point of post-war economic debt and devastation shows that even in times of extreme adversity it is possible to make rapid progress towards UHC.

Secondly, the role of the State was critical at every stage of the UK’s UHC journey – whether in establishing individual rights for those in poverty in the seventeenth century, to the mandating of coverage for lower paid workers in 1911, to the full nationalization of healthcare funding, purchasing and – for hospitals – provision in 1945. Yet there is continueddebate and reform, even in the nation from which the ‘Beveridge Model’ originated, about the appropriate place of government in UHC. There has been a gradual shift in England over the last 50 years to limit the influence of government: reducing its role as a provider through the purchaser-provider split and autonomization of hospitals through Foundation Trust status, and in the last decade relinquishing direct control of purchasing too via the creation of NHS England. Wales and Scotland have resisted these trends, however. So should the state be the provider of UHC, the purchaser, the planner, or perhaps merely the referee? All these questions remain in flux, as they do in a great many other health systems worldwide.

Finally, the work of universal health coverage is never complete, especially for countries like the UK that share an understanding of the concept not as providing some minimum basic safety net for the poorest, but “universalizing the best”[37]. That is, ensuring that high quality healthcare is a collective right that should not be determined by a person’s economic means. Sustaining this in an era of medical advances, rising chronic diseases and ageing populations takes constant work to improve and refine health systems, as well as constant political engagement to continue this quest through good times and bad.

Written by Jonty Roland, Independent Health Systems Consultant jonty@healthforalladvisory.com

With grateful thanks to the work of the ‘History of the NHS Project’ by The Nuffield Trust.

Click here to download the complete article as a PDF document.

Sources:

-

[1] NHS England Statistics, “Prescriptions Dispensed in the Community: 2007 – 2017”, NHS Digital (2019)

-

[2] OECD, “Tackling wasteful spending on health” (page 42), OECD Publishing (2017)

-

[3] Laing Buisson, “Health cover market report”, Laing Buisson (2017)

-

[4] Office for National Statistics, “National Health Accounts 2018” (2018)

-

[5] Department of Health and Social Care, “DHSC annual report and accounts: 2018 to 2019”, UK Government (2019)

-

[6] Solar PM, “Poor Relief and English Economic Development before the Industrial Revolution”. The Economic History Review. 48(1); p1-22 (1995)

-

[7] Sretzer S et al. “Health, welfare, and the state—the dangers of forgetting history”. Lancet. 388(10061); P2734-2735 (2016)

-

[8] Lindert, Peter H. “Poor Relief before the Welfare State: Britain versus the Continent, 1780- 1880.”European Review of Economic History 2. p101-40 (1998)

-

[9] The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834

- [10] Bump J. “The Long Road to Universal Health Coverage: Historical Analysis of Early Decisions in Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States”. Health Systems and Reform. 1 (2015)

-

[11] Digby A & Bosanquet. “Doctors and patients in an era of national health insurance and private practice, 1913‐1938” Economic History Review, p74-94 (1988)

-

[12] Gorsky M, “The NHS in Britain: Any Lesson from History for Universal Health Coverage?” in ed. Medcalf A et al. Health For All: The Journey of Universal Health Coverage. Wellcome Trust (2015)

-

[13] Gorsky M, “NHS at 70 – if original ideals are to be sustained then we need honesty on its running costs”. LSHTM NHS at 70 series (www.lshtm.ac.uk). 14th June 2018.

-

[14] Klein R. The New Politics of the NHS. 3rd ed. Longman; (1995)

-

[15] Pringle, AS. “The National Insurance Act 1911: Explained, Annotated and Indexed.” William Green and Sons (1912)

-

[16] Harris, H. “The British National Health Insurance System, 1911-1919”. Monthly Labor Review. 10(1); p. 45-59. (1920)

-

[17] Digby A & Bosanquet. “Doctors and patients in an era of national health insurance and private practice, 1913‐1938” Economic History Review. xli, i, p74-94 (1988)

-

[18] https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/health-and-social-care-explained/the-history-of-the-nhs/

-

[19] Cherry, S. “Before the National Health Service: Financing the Voluntary Hospitals, 1900-1939”. The Economic History Review. 50(2); p. 305-326 (1997)

-

[20] NHS Scotland, “History of the NHS in Scotland: Highlands and Islands Medical Service”. http://www.ournhsscotland.com/history/

-

[21] Ramsden S & Cresswell R, “First Aid and Voluntarism in England, 1945-85” 20th Century British History. Feb (2019)

-

[22] https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/health-and-social-care-explained/the-history-of-the-nhs/

-

[23] Gorsky M, “NHS at 70 – if original ideals are to be sustained then we need honesty on its running costs”. LSHTM NHS at 70 series (www.lshtm.ac.uk). 14th June 2018.

-

[24] Digby A & Bosanquet. “Doctors and patients in an era of national health insurance and private practice, 1913‐1938” Economic History Review. xli, i, p74-94 (1988)

-

[25] Ibid.

-

[26] Bump J. “The Long Road to Universal Health Coverage: Historical Analysis of Early Decisions in Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States”. Health Systems and Reform. 1 (2015)

-

[27] Abel-Smith B. “The Beveridge Report: its origins and outcomes.” International Social Security Review; 45: p5–16 (1992)

-

[28] https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/health-and-social-care-explained/the-history-of-the-nhs/

-

[29] Gorsky M, “The NHS in Britain: Any Lesson from History for Universal Health Coverage?” in ed. Medcalf A et al. Health For All: The Journey of Universal Health Coverage. Wellcome Trust (2015)

-

[30] https://www.jstor.org/stable/1091419

-

[31] https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-01/between-the-acts-web-final.pdf

-

[32] Commonwealth Fund, “Mirror, Mirror 2017: International Comparison Reflects Flaws and Opportunities for Better U.S. Health Care”. Commonwealth Fund (2017)

-

[33] Department of Health and Social Care & HM Treasury, “Prime Minister sets out 5-year NHS funding plan”. 18 June 2018.

-

[34] Nuffield Trust, Kings Fund & Health Foundation, “£4 billion needed next year to stop NHS care deteriorating”. Nuffield Trust Press Release, 8th November 2017.

-

[35] Kings Fund, “Public satisfaction with the NHS and social care in 2019: Results from the British Social Attitudes survey”. Kings Fund, (2020).

-

[36] Opinium, “Pride of Britain list”. Opinium (2016)

-

[37] Gorsky M, “The NHS in Britain: Any Lesson from History for Universal Health Coverage?” in ed. Medcalf A et al. Health For All: The Journey of Universal Health Coverage. Wellcome Trust (2015)