Universal health coverage (UHC) and universal social protection (USP) are complementary objectives embedded in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. With only few years left to meet the SDG targets, it is urgent to strengthen those synergies. Health and wellbeing should not be the privilege of a few. Equitable and solidarity-based social protection is central to facilitate financial access to health care services and address the socio-economic inequalities that impact on health outcomes.

Key messages:

- Social protection is a redistributive mechanism to protect people against social and economic risks, as such it can make an important contribution to a broader shift towards an economy that promotes human health and well-being within planetary boundaries.

- Comprehensive protection throughout the life cycle and adequate benefit levels are needed to maximize the health impact of social protection policies.

- Social health protection can and should support levelling the playing field when it comes to equity in access to healthcare services, lifting financial barriers and supporting primary health care.

- Social health protection policies are an empty promise if healthcare services are not accessible, available, acceptable and of good quality. Greater coordination with the health sector and joint advocacy for investments in healthcare and the health workforce are needed.

The United Nations General Assembly recalled in September 2023 the fundamental importance of social protection mechanisms to meet the objective of Universal Health Coverage (UN, 2023). Social protection systems, including floors, support health and wellbeing by providing:

- access to healthcare without hardship – addressing financial barriers and promoting care seeking; and

- income security throughout the life course – addressing some of the social determinants of health equity.

Social health protection to protect people against healthcare costs

Social health protection refers to government-led measures to secure affordable healthcare services and adequate cash benefits for all in case of sickness (ILO, 2020b). Countries such as Rwanda or Lao PDR have shown that extending social health protection is achievable even in low-income settings (ILO, 2021c). Their experience demonstrates that a sustained political and financial commitment embedded in a rights-based approach is indispensable to leave no one behind.

While social health protection has expanded over the last decades, important inequalities persist across and within countries.

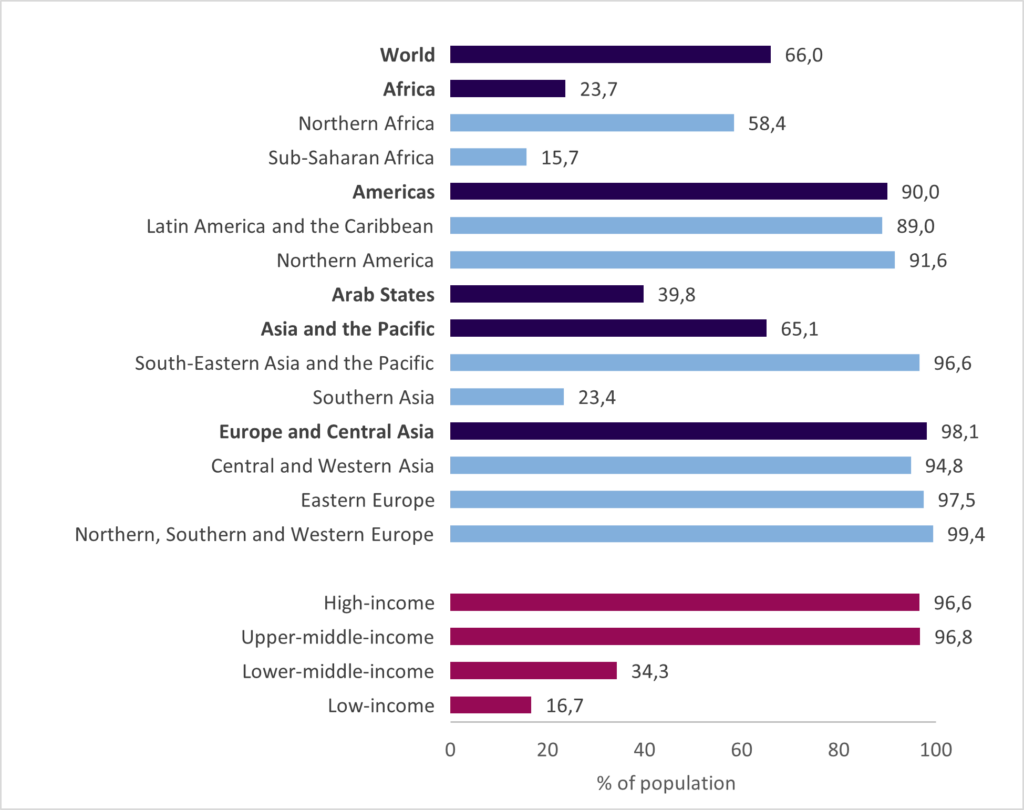

The data we are currently compiling for the forthcoming World Social Protection Report, which will be released in September 2024, puts it in sharp focus. A review of legal frameworks shows that globally eight in ten people have a right to access healthcare services for free or with limited co-payments (ILO forthcoming). However, in low-income countries, only six in ten people have this right according to their national legislation. There is a further gap between those legal entitlements and their implementation in practice, resulting in a situation where less than a fifth of the population is effectively protected by a social health protection scheme in low-income countries.

Figure 1: Percentage of the population covered by a social health protection scheme (protected persons), by region, subregion and income level, 2020 or latest available year.

Source: ILO (2021) and OECD Health Statistics (2020); national administrative data published in official reports; information from regular national surveys of target populations on awareness on rights.

In this context, it is no surprise that out-of-pocket spending on healthcare is increasing, with 1 billion people facing catastrophic spending and almost 1.3 million pushed into poverty in 2019 (WHO and World Bank, 2023). Without social health protection, the most vulnerable may not even seek medical care. Financial barriers remain a lead reason for forgoing care (WHO and World Bank, 2023). Effective access is further constrained by shortages of healthcare services and their inequitable distribution. The majority of the world’s population is not able to access the minimum package of healthcare services guaranteed by international social security standards, with the biggest deficits in Africa and Asia (ILO, 2021c).

Those figures hide important inequalities within countries. For instance, the lack of resources to pay for health services is identified as a main reason for forgoing care among women in reproductive age in 58 low- and middle-income countries, following a clear social gradient: two thirds of women in the lowest income quintile forego care for this reason, while this is the case for less than a third in the richest quintile (WHO and World Bank, 2023).

Urgent action is needed along four priority areas towards 2030:

- Extend social health protection universally. Several countries in Africa, such as Comoros, Ivory Coast, Morocco and Sierra Leone demonstrated their commitment thereof through the recent adoption of legislation on universal health coverage and subsequent ratification of ILO Convention No. 102. Effective implementation is not easy. Countries need to take advantage of the opportunities created by digital tools, support shared registries across social policies and reinforce a culture of mandatory coverage (ILO, 2021a). In turn, financing arrangements should not be used as eligibility criteria. Where social contributions or regulated premiums are used to finance social health protection, non-contributory mechanisms must be in place to guarantee coverage for those with insufficient contributory capacities and reach universality.

- Ensure equity. Social health protection can and should support levelling the playing field to ensure equity in access to adequate healthcare services, particularly in primary care settings. Women, people living with chronic conditions, long-term diseases or disabilities, older persons, workers in vulnerable employment and migrants tend to face multiple barriers to access social health protection. Their needs must be at the center of the design, implementation, financing and participation modalities for extension. Social health protection can also bring more equity in fragile settings and support bridging the humanitarian-development nexus (ILO and UNHCR, 2020b). Countries such as Rwanda and Kenya pledged to include refugees at par with nationals in their social health protection schemes with a view to ensure greater access to health services and improve the health status of refugees and host communities alike (ILO and UNHCR, 2020a).

- Improve adequacy. Social health protection policies are an empty promise if healthcare services are not accessible, available, acceptable and of good quality. Collaboration across responsible institutions under the stewardship of the Ministry of Health is needed. Securing the supply of healthcare services requires to secure decent work for the health workforce in line with international labour standards[1]

(High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth, 2017). From an operational standpoint, it is crucial that funding commensurate to service demand flows in healthcare facilities. Robust management information systems that are both affordable and provide a good interface at the healthcare facility level are needed. - Secure sustainable financing based on the principle of solidarity. The ILO, in collaboration with the WHO, estimated the financing gap for social protection floors, including in health, which will be released this April at the Financing for Development forum. In this context, innovative solutions are needed to prioritize social protection and health within government budgets, but to also expand fiscal space through a diversified mix (ILO, 2021a). In doing so, governments need to pay attention to equity and secure progressive sources of public revenues (Durán Valverde et al., 2019).

Health and wellbeing should not be the privilege of a few. Collective financing, broad risk pooling and rights-based entitlements are key elements of strong social health protection systems geared towards social justice. Practical tools exist to extend coverage. More broadly, overcoming inequalities requires addressing comprehensively financial protection against the costs of illness, covering not only the costs of services but also non-medical costs such as transportation and lost income during recovery, that are key determinants of health equity (ILO 2021b; 2020a).

Universal social protection to support health equity throughout the life course

Health and wellbeing are strongly determined by the conditions in which people live, work, grow and age (Marmot, 2001). Income insecurity, poverty, vulnerability, and social exclusion have significant negative impacts on health, affecting and food security, education, housing, healthcare seeking behaviours, and other social determinants of health. Health outcomes, such as infant mortality rates, lifetime risks of maternal death during pregnancy and post-partum, as well as lifetime risk of long-term disabilities are higher in LMICs than in HICs, but also tend to be higher for social groups with low education levels and at the lower end of the income distribution within countries (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008). Evidence suggests that social determinants of health may account for as much as 50 percent of health outcomes, with significant inequities (WHO, 2024). Global mega-trends such as climate change and health security threats are reinforcing existing social and economic inequalities that are responsible for health and wellbeing inequity globally and locally (Jay and Marmot 2009).

Social protection contributes to address the social determinants of health equity, with an important role for adaptive social protection in the current climate crisis context. Impact assessments have shown the positive impact of social protection on both healthcare seeking behaviour and health outcomes, for example for family benefits such as Bolsa Familia in Brazil (de Andrade et al., 2015). Moreover, unemployment insurance has positive impacts on health, including mental health (Kuka, 2020). Income support has demonstrated impact on prevention, detection and adherence to treatment in the context of HIV and tuberculosis (WHO and ILO, 2024; ILO, 2021b). More broadly, in the WHO EURO region 35% of the inequity in self-reported health between those who are most and least affluent is due to “systematic differences in risk and exposure to income insecurity and the lack or inadequacy of social protection” (WHO, 2019).

To maximise the impact of social protection on health and wellbeing, we put forth two actionable priorities:

- Extending comprehensive protection against life cycle risks to all. Social protection systems that achieved high population coverage prior to the onset of COVID-19 were more effective in responding to the pandemic and other epidemics than those with narrow coverage (ILO, 2021c). Some types of benefits such as sickness and maternity need to be prioritized as they lag behind globally. With more than half of the world population not covered by any social protection benefit, we urgently need to change gear towards a human-centred policy agenda (ILO, 2021c).

- Securing adequate benefit levels to effectively support income security. A global review of evidence on the COVID-19 response has shown that social protection programmes have a positive role in cushioning the socio-economic impacts of public health and social measures (PHSM), especially went they offer an adequate level of benefits (WHO Forthcoming). PPR strategies should include social protection and support sustainable social protection systems providing adequate levels of benefits (USP2030, 2023).

No UHC without USP and vice-versa

Achieving universal social protection that fosters individual and societal resilience requires a rights-based approach. Such approaches support the predictability, transparency, and accountability in delivery of entitlements for right-holders, promoting sustainable entitlements over time that are resilient to short-termism. Social protection systems are crucially important to address the social determinants of health whilst preventing people from facing financial hardship when accessing healthcare services, or foregoing care altogether. As a redistributive mechanism geared towards protecting people against social and economic risks, social protection policies can make an important contribution to a broader shift towards an economy that promotes human well-being and remains within planetary boundaries.

[1] Including the Medical Care Recommendation No. 69 of 1944, the Nursing Personnel Convention No. 149 of 1977 and its Recommendation No. 157, and the Domestic Workers Convention No. 189 of 2011.

Andrade, Luiz Odorico Monteiro de, Alberto Pellegrini Filho, Orielle Solar, Félix Rígoli, Lígia Malagon de Salazar, Pastor Castell-Florit Serrate, Kelen Gomes Ribeiro, Theadora Swift Koller, Fernanda Natasha Bravo Cruz, and Rifat Atun. 2015. ‘Social Determinants of Health, Universal Health Coverage, and Sustainable Development: Case Studies from Latin American Countries’. The Lancet 385 (9975): 1343–51.

Commission on Social Determinants of Health, WHO. 2008. ‘Closing the Gap in a Generation – Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health – Commission on Social Determinants of Health Final Report’. WHO.

Durán Valverde, Fabio, José Pacheco-Jimenez, Taneem Muzaffar, and Hazel Elizondo-Barboza. 2019. ‘Measuring Financing Gaps in Social Protection for Achieving SDG Target 1.3: Global Estimates and Strategies for Developing Countries’. ESS Working Paper No. 73.

High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth. 2017. ‘High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth’. WHO.

ILO. 2020a. ‘Sickness Benefits: An Introduction’. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

ILO. 2020b. ‘Towards Universal Health Coverage: Social Health Protection Principles’. Social Protection Spotlight. Geneva: ILO.

ILO. 2021a. ‘Extending Social Health Protection: Accelerating Progress towards Universal Health Coverage in Asia and the Pacific’. Regional Report. Bangkok and Geneva: ILO.

ILO. 2021b. ‘Making Universal Social Protection a Reality for People Living with, at the Risk of, and Affected by HIV or Tuberculosis’.

ILO. 2021c. World Social Protection Report 2020–22: Social Protection at the Crossroads – in Pursuit of a Better Future. Geneva.

ILO. Forthcoming. World Social Protection Report 2024–26.

ILO and UNHCR. 2020a. ‘Handbook on Social Health Protection for Refugees: Approaches, Lessons Learned and Practical Tools to Assess Coverage Options’. Geneva: International Labour Organization and UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

ILO and UNHCR. 2020b. ‘Social Protection in Action: Exploring Public Options of Social Health Protection for Refugees in West and Central Africa’.

Jay, M, and MG Marmot. 2009. ‘Health and Climate Change’. The Lancet 374 (9694): 961–62.

Kuka, Elira. 2020. ‘Quantifying the Benefits of Social Insurance: Unemployment Insurance and Health’. Review of Economics and Statistics 102 (3): 490–505.

Marmot, Michael. 2001. ‘Economic and Social Determinants of Disease’. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 79: 988–89.

UN. 2023. ‘Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage “Universal Health Coverage: Expanding Our Ambition for Health and Well-Being in a Post-COVID World”’.

USP2030. 2023. ‘Maximizing the Positive Health Impacts of Social Protection for Epidemic and Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness, and Response: Emerging Principles’. Global Partnership for Universal Social Protection to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (USP2030).

WHO. 2019. ‘Healthy, Prosperous Lives for All: The European Health Equity Status Report’. Copenhagen: World Health Organization – Regional Office for Europe.

WHO. 2024. ‘Operational Framework for Monitoring Social Determinants of Health Equity’. Geneva: World Health Organisation and International Labour Organisation.

WHO. Forthcoming. ‘Reducing the Socio-Economic Burden of Public Health and Social Measures on Households during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Landscape of the Evidence on the Role of Social Protection Policies and Programmes’. Geneva: World Health Organization.

WHO and ILO. Forthcoming. ‘Guidance on Social Protection for People Affected by Tuberculosis’. Geneva.

WHO and World Bank. 2023. ‘Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2023 Global Monitoring Report’. Geneva: World Health Organization.