Decisions by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members to freeze or cut aid disrupt health services in low- and middle-income countries, risking a 40% drop in health aid by 2025 and worsening workforce shortages, especially in Africa.

Background

The 2025 decisions by members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) to freeze or cut official development assistance (ODA) has created a significant disruption in the global aid ecosystem and national political agendas of low- and-middle income countries (LMICs). This situation has had immediate consequences for the availability of critical health services, commodities and health and care workers across LMICs. A rapid assessment by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2025 found that over half (63%) of WHO country offices reported job-related effects on health and care workers in countries. Budget cuts are expected to reduce countries’ ability to absorb new health and care workers, worsening existing shortages. With reduced absorptive capacity, health systems in Africa are projected to see an increase in the health and care workforce shortage of 600,000 health and care workers by 2030, compared to earlier estimates.[1]

Various attempts have been made to estimate the implications of these recent decisions from input, output, organizational or disease-specific perspectives; still, there is limited understanding of the financial impact for ODA in the health sector as a whole. This blog post is a first attempt to examine the potential magnitude of the health funding cliff in order to facilitate informed decision-making by both donors and recipient countries. This review can inform global and country leaders as they work to respond and adjust to the funding shifts, particularly in LMICs where ODA has been the main source of health funding.[2]

Method

Key findings

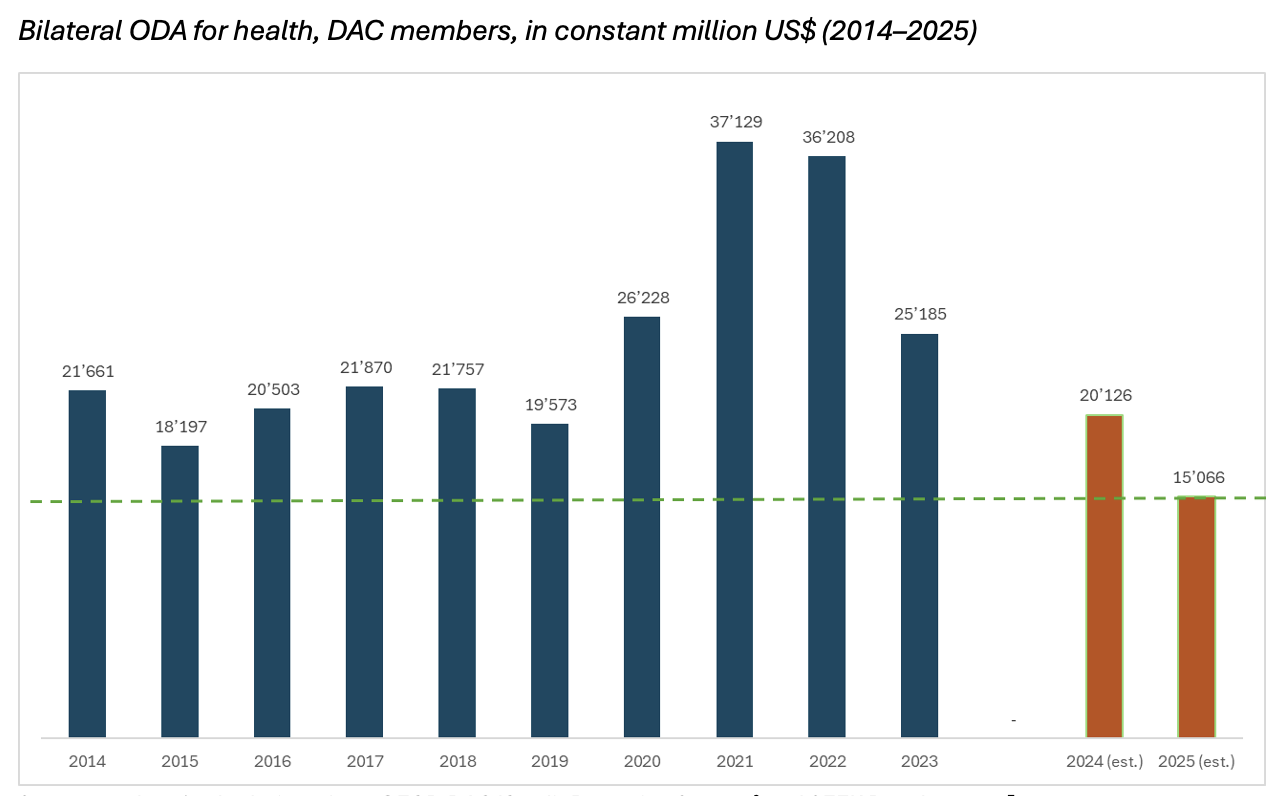

The key finding of this assessment is that DAC ODA for health, assuming no adjustments in the allocations to health, could decline by 40% in 2025 compared to the 2023 baseline, with potential decreases from the US$ 25.19 billion disbursed in 2023 to US$ 15.07 billion in 2025. This reduction would bring DAC ODA for health substantially below the average over the past decade (US$ 24.83 billion from 2014-2023) and below its lowest level during that period (US$ 18.20 billion in 2015).[6]

Note: The data include bilateral disbursements plus inputted multilateral aid from DAC members (countries and EU institutions) to recipients for health sector ODA, downloaded on 17 March 2025 from OECD Data Explorer.

Estimating the financial impact of public announcements by donor governments on ODA for health is challenging due to numerous uncertainties, including: (1) new expected decisions by governments regarding the future of their ODA volume (for example, whether the American government freezing may lead to definite cuts) and (2) potential changes in sectoral and geographic priorities (meaning, whether health or certain components of health will be de- or reprioritized).[8] This means the figures provided in this blog only indicate the potential size of the financial effect, rather than actual reductions in overall health aid funding in countries. Future commitments to multilateral health agencies (like, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, International Development Association / World Bank Group) will also likely change the level of actual health funding available in recipient countries.

Complementary takeaways

While understanding the magnitude of the decline in overall ODA for health is crucial and likely serves as an important wake-up call for many, we want to convey four complementary messages.

- First, the decline in DAC ODA for health, although significant, should be viewed within the broader context of overall ODA reduction. The COVID-19 crisis, combined with the war in Ukraine, triggered an unprecedented rise in DAC ODA for health, peaking at US$ 37.13 billion and US$ 36.21 billion in 2021 and 2022, respectively. Preliminary data from 2024 indicate that DAC ODA was already returning to pre-COVID-19 levels (US$ 21.87 billion in 2017, US$ 21.76 billion in 2018 and US$ 19.57 billion in 2019). Moving forward, it is essential to continue to improve monitoring ODA dynamics closely to provide better, more transparent and more granular data on ODA for health, including tracking of country-level spending through National Health Accounts.[9]

- Second, we should not expect that domestic resources need to compensate ODA on a one-to-one dollar basis to achieve the same outcomes. As discussed elsewhere and echoed by many country leaders, this immediate crisis may be a catalyst for broad efficiency gains and transformative change in health systems. In this context, realigning and reorganizing health systems, both in terms of financing (for example, reducing off-budget, parallel funding) and service delivery (as in, shifting away from vertical approaches and moving towards integrated, primary health care–centered services), in line with the Lusaka Agenda, is an impetus.

- Third, in this context, building a sustainable and fit-for-purpose workforce will face additional challenges. Moving forwards, countries will need to assess the impact of the current funding shifts on both direct and indirect job losses, and explore budget space for creating sustainable employment opportunities for health and care workers to meet health systems needs, in the line with the global action plan for health and care workforce.

- Last, global action is needed to refine ODA for health modalities, by combining loan and grant financing sources (for example, from global health initiatives) to increase the directionality and concessionality of financing and to crowd-in domestic spending in line with the the Financing for Sustainable Development proposal. Time-limited, transitional financing can be used to set the right incentives for donors, recipients and implementers and equip countries with the greatest needs to build systems for self-reliance.

Acknowledgements: Pascal Zurn (WHO Health Workforce Department) and Fahdi Dkhimi (WHO Health Financing and Economics Department) compiled the data and produced the estimates; Hélène Barroy (WHO Health Financing and Economics Department) and Pascal Zurn drafted the blog post; Susan Sparkes (WHO Health Financing and Economics Department), Juana Paola Bustamante (WHO Health Workforce Department), Jim Campbell (WHO Health Workforce Department) and Kalipso Chalkidou (WHO Health Financing and Economics Department) provided input to and comments on the text.

The team acknowledges the technical support and review provided by Julien Dupuy, Xu Ke (WHO National Health Accounts), Anna Vassall (WHO Economic Evaluation and Analysis), Khassoum Diallo and Mathieu Boniol (WHO Data, Evidence and Knowledge Management).

References

[1] In the African region, the health workforce gap was projected to decline from 5.9 million in 2023 to 5.6 million by 2030. However, with reduced absorptive capacity, that shortage is now expected to rise to 6.2 million by 2030.

[2] World Health Organization, Global spending on health: Emerging from the pandemic

[3] The focus of these estimates is on bilateral aid (meaning, disbursements from OECD DAC donors to recipient countries), excluding multilateral and philanthropic-related disbursements.

[4] The analysis uses “disbursement” data as defined by OECD DAC/Creditor Reporting System (as in, payments made by DAC member countries to recipient countries).

[5] For the year 2024, linear interpolation was used, as official data were not available at the time of writing this blog.

[6] OECD, Development finance statistics: Resources for reporting. DAC data include a deflator for “total DAC” flows. This is the average of the deflators of individual DAC donors, weighted by each donor’s total ODA (base year 2022).

[7] A repository of government announcements is available on The Budget Cuts Tracker.

[8] Justin Sandefur and Charles Kenny, USAID Cuts: New Estimates at the Country Level, GCD. Emerging evidence seem to confirm differentiated effects of aid cuts on and within sectors. While the American freeze is expected to result in a 38% cut overall, certain areas of health are expected to be hit the greatest (for example, 94% for family planning and reproductive health).

[9] World Health Organization, Strengthening health financing globally. The recently proposed World Health Assembly resolution to strengthen health financing globally brings hope in this respect, with a call to establish an ODA for health tracker that can transparently track, monitor and report on both the amount of ODA for health and how it is channeled.