Kéfilath Bello, Fadhi Dkhimi, Y-LingChi, Jean-Paul Dossou, HélèneBarroy

On May 20, 2021, WHO, P4H, the Center for Global Development, the Global Financing Facility (GFF) and Collectivity have organized a webinar entitled ” COVID-19 : what impact on the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) agenda in African countries ? Drawing on discussions that involved over 200 participants, our team takes a closer look at some of the issues and invites experts from French-speaking Africa to reflect collectively.

Over the past decade, a number of low- and middle-income countries (including many in French-speaking Africa) have been making considerable progress towards universal health coverage (UHC). These countries have shown that strong political will is an essential prerequisite for achieving this goal. This political will must also translate into into a series of coordinated reforms aimed at better mobilization of public funds for healthcare, greater pooling of these resources, and ways of purchasing services that improve the quality and efficiency of healthcare services and ensure greater equity in their distribution.

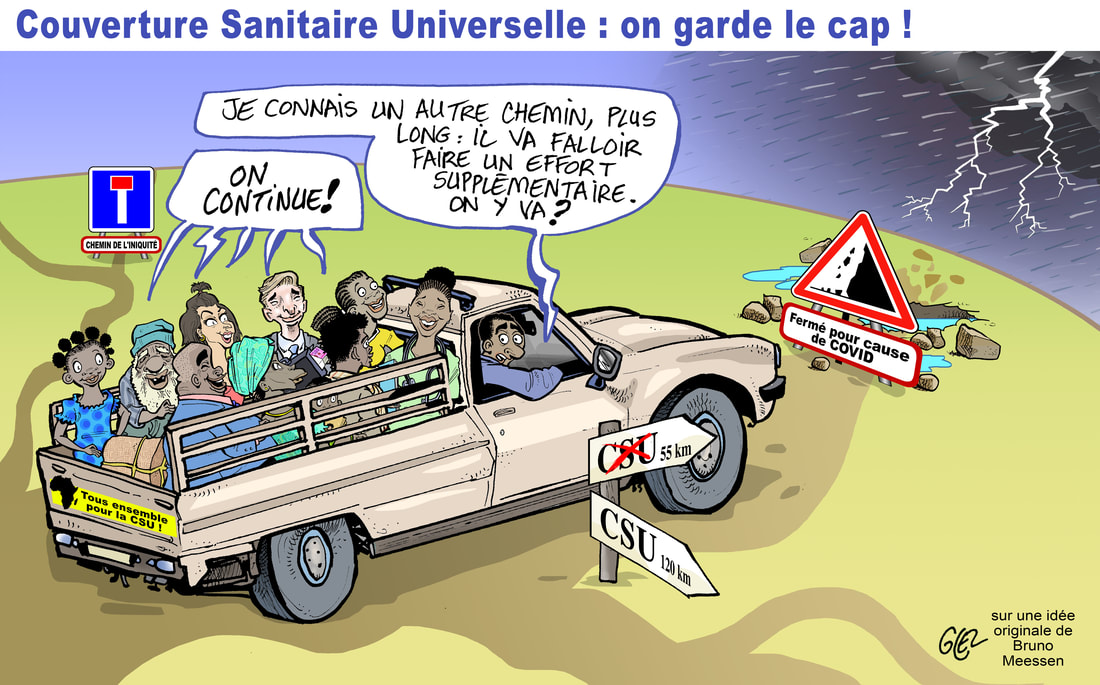

The COVID-19 pandemic, by accentuating the weaknesses of healthcare systems, recalled the need to reinforce this agenda. The issue of access to healthcare for all has thus gained a higher profile on the political agenda. But while the crisis has highlighted the need to speed up progress towards the CSU, it could also disrupt the chances of implementing such an ambitious project.

More challenges in the COVID-19 era to achieve universal health coverage

While it served as a reminder of the urgency and relevance of ensuring CSU, the crisis linked to COVID-19 paradoxically risks making progress towards this objective more difficult.

A decline in the availability of public resources

COVID-19 is also an economic crisis which has, and will continue to have, a major impact on public funding for the healthcare sector in sub-Saharan Africa, as in other regions of the world. Visit projections by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) point to a significant 6.2% drop in GDP in sub-Saharan Africa in 2022 compared to 2020, twice the world average (3.7%).

This contraction in the economy has major fiscal consequences, leading to a substantial drop in government budget resources in the short and medium term. Visit projections indicate that domestic public revenues could fall to a level below that of the 2009 crisis (to 15.6% of GDP on average in the region according to current projections, versus 18.4% in 2009). This is due not only to a decline in tax revenues, but also to a sharp drop in the borrowing capacity of sub-Saharan African states caused by the deterioration of their credibility on financial markets – 23 countries are either in debt distress or at high risk of debt distress, according to the IMF’s June 2021 estimates, compared with 15 in April 2019 as indicated by the UNECA annual report.

To date, there is no certainty that the reduction in public revenues will be offset – at least in part – by external public aid. Of course, the latter experienced a unprecedented global increase in 2020But donor countries, which have borrowed heavily to cope with the health crisis caused by COVID 19 and its economic fallout, are going to have to repay – or continue borrowing if the crisis continues – and therefore reduce their public spending to do so. External aid is often one of the budgetary envelopes most quickly allocated in the event of a crisis, because political decision-makers – and taxpayers too – consider it to be less of a priority than other budget items. It’s not impossible, therefore, that donor countries will quickly scale back their commitments, as they have done in the past. already the case in Great Britain for example. If foreign aid falls, this would also reduce the funds available in the form of subsidized borrowing, one of the most widely used aid mechanisms, further reducing the borrowing capacity of Sub-Saharan African countries.

Lower healthcare benefits ?

If public resources fall, it is legitimate to ask whether this will have an impact on budget allocations to the healthcare sector. The sector’s needs have increased, but what about budget allocations ? A legitimate increase could be expected in view of the sector’s needs to respond to the aftermath of the epidemic, while continuing to provide essential routine care. However, the data analyzed show that the year 2020 was not marked by a sharp increase in healthcare budget allocations in African countries, compared with the United States. significant increases in high-income countries, for example. Existing data show that budget allocations have increased by an average of 10% in the region by 2020. This may be explained by the low prevalence of COVID-19 reported in the region in 2020.

What about 2021 ? It’s hard to predict what’s going to happen next. Available budget documents seem to point to a moderate increase in budget allocations for healthcare, especially in low-income countries. If public spending on healthcare was $8.3 per head before COVID-19 (GHED 2018 baseline) in low-income African countries, budget allocations would rise to $12.8 in 2021. In middle-income African countries, these allowances would rise from $92.5 to $94.8. The year 2022 and beyond will be crucial in determining the sustainability of budget increases in the sector.

The countries affected by the Ebola crisis in 2015 offer an interesting perspective on this point. In one country Like Sierra Leone, Ebola led to a sudden rise in the share of domestic health spending in the government budget, and although this level has not been maintained, it remains higher today than before the crisis.

Persistent structural challenges and an increasingly difficult socio-political and security context

Several observations indicate that the pandemic has exacerbated the structural challenges facing healthcare systems in French-speaking Africa. A WHO study (end 2020) and other estimates show, for example, that the pandemic has severely compromised the quality of care and the availability of health services and personnel. Household financial protection could also deteriorate considerably, as the current economic situation could tip the balance in favour of the private sector. more than 150 million people living in extreme poverty by the end of 2021. What’s more, in many countries (where data is available), particularly in India), it would appear that COVID-19 coverage is associated with significant household expenses.

In addition to these structural challenges, French-speaking Africa is also confronted with new challenges such as terrorism, socio-political crises and climate change, with consequences such as population displacement and the weakening of state institutions. The pandemic has also brought back (and even exacerbated) the chronic crisis of confidence between the public and political leaders, with little faith in official national and international discourse. This was particularly evident in scepticism about the reality of the epidemic, and mistrust of the COVID-19 vaccine. These contextual difficulties could act as an additional brake, as they leave little room for maneuver to launch the investments required for the CSU.

Moving forward despite (and with) COVID-19

Despite COVID-19, several French-speaking African countries seem intent on staying the course towards CSU (or at least continuing the efforts already underway). Benin, for example, is extending its health insurance program for the poorest. Likewise, Togo has stayed the course towards the co-creation of an integrated plan for the CSU and the launch of a free health care for pregnant women. Similar examples were reported by participants . webinar organized by WHO and its partners in May 2021. What’s more, beyond its negative consequences, COVID-19 has opened up new perspectives. The impact of the pandemic on a number of business sectors prompted some governments to take immediate action. multi-sectoral actions coordinated at the highest level, an approach long advocated with little success for primary healthcare and the CSU. Some countries have also seized these opportunities to become even more committed to the CSU.

However, the challenges described above are likely to lead to a situation in which needs grow, but the resources to meet them diminish. Despite these challenges, countries should not allow themselves to be tempted by solutions that seem attractive (increasing co-payments, for example), but have been shown to be ineffective and sometimes unfair. On the contrary, the States of French-speaking Africa will have to make judicious choices, guided by the principles of solidarity invoked by the CSU. These choices would enable us to make the best possible investment of available resources, win the trust of our populations and strengthen our healthcare systems in the long term.

But how can French-speaking African countries achieve such a feat?

While it’s not possible to prescribe a recipe for every country, several lessons have been learned from past experience. One course of action would be to adopt a pragmatic approach to identifying key high-value-added services on which to focus initially. For example, Chile’s “AUGE” reform aims to provide access to a defined package of services for the entire population. This package was initially limited to priority services, but is reviewed every two years on the basis of cost studies, health priorities in the country and budgetary space. A gradual approach to service expansion may be difficult to implement, but it seems the least risky in the short to medium term.

Other courses of action and principles are being discussed today by a number of health financing experts, notably in a report published in 2019 by the WHO and in an article published in August 2021. Some of these tracks are :

- To mobilize resources, give preference to compulsory or automatically-levied sources of funding (e.g. taxes) rather than voluntary contributions;

- For resource pooling, reduce the fragmentation of funds to improve the ability to redistribute resources and increase efficiency;

- Invest in population-focused interventions of general benefit to health, such as water and sanitation, health-promoting taxes and a high-performance epidemiological information and surveillance system ;

- Increase the multi-year predictability of available public funding and make the flow of public funds more stable;

- Implement targeted policies aimed at increasing the efficiency of healthcare expenditure (e.g. the purchase of medicines, which represent a major budget item in all countries);

- Put equity at the heart of CSU action by adopting strategies that guarantee access to services and protection for vulnerable people, for example by targeting certain populations and services;

- Establish formal (and enshrined in legislation) processes for adopting and regularly reviewing the benefits package. Any additions must be based, as a minimum, on an analysis of cost-effectiveness and budgetary impact;

- Explain the benefit package to the public in easy-to-understand terms, using appropriate communication media;

- Move progressively towards more strategic purchasing of healthcare services, increasing over time the extent to which payment to providers is determined by information about their performance and the health needs of the population they serve;

- Strengthen multi-sectoral action, in particular collaboration between health authorities, finance authorities and authorities in sectors that can have an impact on health.

Whatever options countries choose, the decisions they take will have to be framed by a high-quality political dialogue that includes key stakeholders and ensures that needs are genuinely taken into account and that accountability is transparent. Faced with the great uncertainty surrounding these decisions, countries will also need to adopt a learning attitudein which they test, evaluate and adapt their chosen strategies.

Click here to access the original article.